Today is Bastille Day, a celebration of the start of the French

Revolution. Most people I’ve talked to who have issues with the Revolution point

to its violence. It’s difficult to overstate the violence of the Revolution.

You could look at the sheer number of people beheaded with the guillotine, a

device chosen for being painless and disturbingly efficient.[1]

Less illuminating, but more emotionally charged, are anecdotes like the episode

in which a mob broke into the royal palace at Versailles, took the royal family

hostage, and forced them to ride to Paris in a parade with the still-bleeding heads

of their household staff, mounted on pikes. The bloodiness of the French

Revolution is clearly horrific, and it’s enough to make a person skeptical

about the Revolution’s cultural impact. A characterization of the Revolution

that seems fairly common to me is that it was good in theory, but then it got

out of control. I’m skeptical about this conception of the revolution. Looking

at the foundational documents of the revolution show all sorts of problems in

the ideals of the revolutionaries, to the point where it seems reasonable to

think that the ideals were part of the reason the revolution went out of

control.

Today is Bastille Day, a celebration of the start of the French

Revolution. Most people I’ve talked to who have issues with the Revolution point

to its violence. It’s difficult to overstate the violence of the Revolution.

You could look at the sheer number of people beheaded with the guillotine, a

device chosen for being painless and disturbingly efficient.[1]

Less illuminating, but more emotionally charged, are anecdotes like the episode

in which a mob broke into the royal palace at Versailles, took the royal family

hostage, and forced them to ride to Paris in a parade with the still-bleeding heads

of their household staff, mounted on pikes. The bloodiness of the French

Revolution is clearly horrific, and it’s enough to make a person skeptical

about the Revolution’s cultural impact. A characterization of the Revolution

that seems fairly common to me is that it was good in theory, but then it got

out of control. I’m skeptical about this conception of the revolution. Looking

at the foundational documents of the revolution show all sorts of problems in

the ideals of the revolutionaries, to the point where it seems reasonable to

think that the ideals were part of the reason the revolution went out of

control.

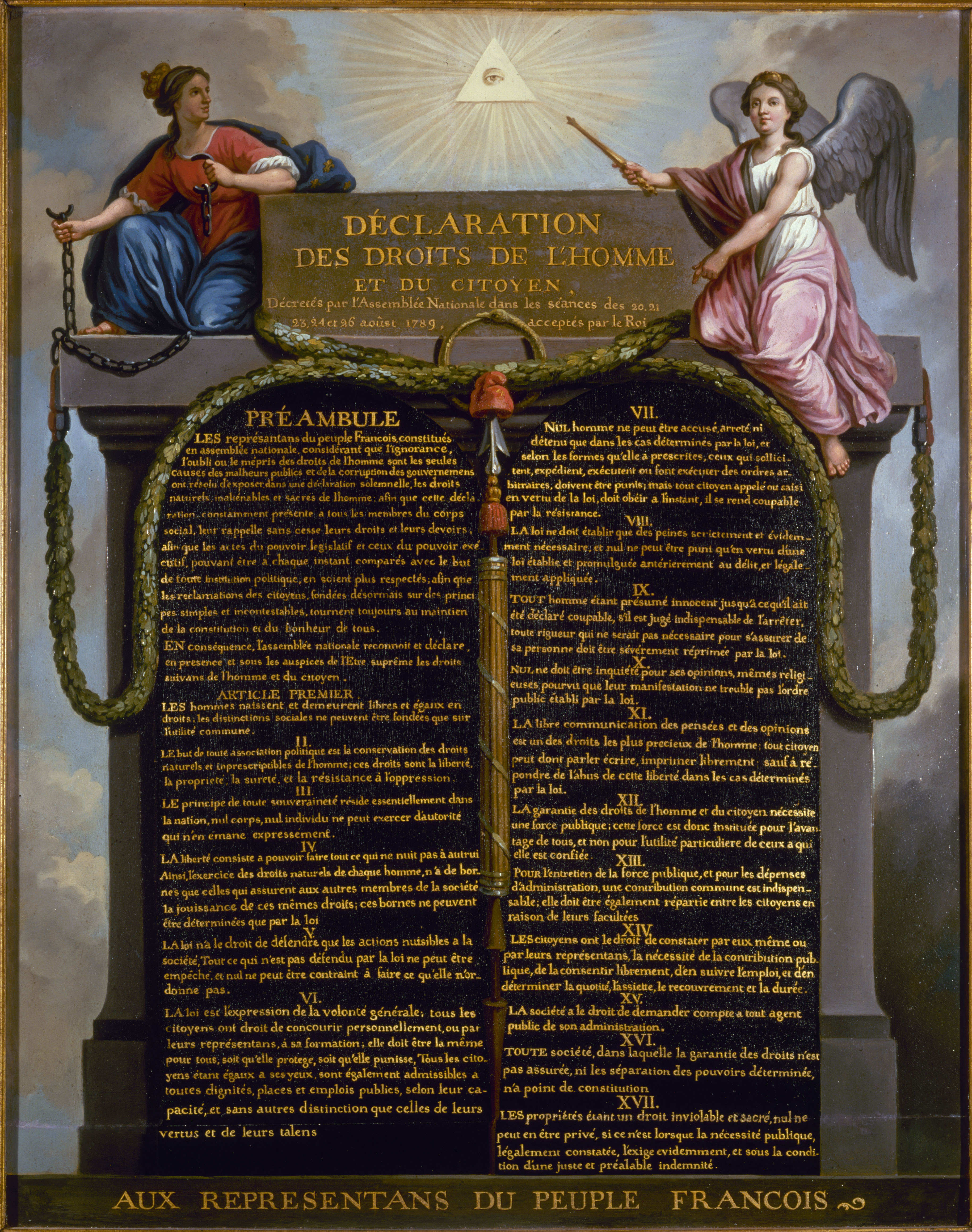

The most

obvious example of this is the type of rights language the Declaration of

Rights of Man and Citizen (a sort of preliminary Bill of Rights). Some of these

sound like nice ideas that most people in modern in society can get behind,

like the idea that “The free communication of ideas and opinions is one of the

most precious of the rights of man.” Free speech! We all like free speech. But

much of the rest of the document is vague. For instance, it asserts that all sovereignty

is derived from the nation. Nationalism was a fast-growing, popular idea in

Europe at the time, so presumably this refers to some nationalist catchphrase,

but the actual point to this (besides to say that sovereignty didn’t come from

the King) is left out.

The document also asserts that “Men

are born and remain free and equal in rights.” This is taken right out of

Rousseau’s philosophy, similar to the way the American Founding Fathers

borrowed Locke’s ideas. But what “Men are born free” means has always eluded me.

The meaning wasn’t obvious to people of the time either. The British political

philosopher Jeremy Bentham criticized the pronouncement harshly: “All men

are born free? All men remain free? No, not a single man: not a single man

that ever was, or is, or will be. All men, on the contrary, are born in

subjection, and the most absolute subjection—the subjection of a helpless child

to the parents on whom he depends every moment for his existence. In this

subjection every man is born—in this subjection he continues for years—for a

great number of years—and the existence of the individual and of the species

depends upon his so doing.” A more positive way of putting it is that we are

born into this world with dependency, relationships, and duties. A newborn

infant clearly can’t do anything he wants, because he can’t even feed himself.

Similarly, his parents do not “remain” free because they are bound by basic

obligations to care for their child—a basic obligation we would hope would be

more of a springboard for the greater relationship springing from mutual love.

However, even without this love, it would be considered reprehensible if the

parents left the child in the woods to die. These sort of basic obligations, or

duties, are a part of natural law; because of the nature of the parent-child

relationship, the parent must provide for the child, at least insofar as she or

he is able. Natural law can also be the basis for rights; in the case of the parent

and child, we could say that the child has a right to be cared for.

I won’t say natural law theory can’t

be interpreted in ways that vary. However, it is useful to compare the French

Revolutionaries’ idea of rights with natural law. Natural law is a possible basis we can

appeal to to justify claims of rights. The revolutionaries offered no grounds

for their rights. Rights were simply asserted as obvious, even though they

would have been considered absurd mere centuries before. The government didn’t

provide for those rights, so the revolutionaries overthrew the government and

set up a new one. Where do these rights come from? Bentham asks, “What, then,

was their object in declaring the existence of imprescriptible rights, and without

specifying a single one by any such mark as it could be known by? This and no

other—to excite and keep up a spirit of resistance to all laws—a spirit of

insurrection against all governments—against the governments of all other

nations instantly,—against the government of their own nation—against the

government they themselves were pretending to establish—even that, as soon as

their own reign should be at an end.” In other words, if these rights are

merely asserted without any clear basis, how do we know what rights ought to be

claimed? What rights correspond to the vast network of human relationships we

call society? Without a basis for rights besides popular opinion, we wind up

with an explosion of rights. Rights could be asserted even though they have no

apparent basis in our natures.

This explosion of rights is a much

more far-reaching effect of the revolution than the temporary, though horrific, violence. Rights eventually conflict with not

only our natures, but the rights of others. The right to freedom of religion

was found to conflict with the public welfare; since the freedom of religion

had no particular basis (or at least none was given at the time), it folded.

Catholic churches were burned, priests beheaded, monasteries attacked. The

revolutionary government founded a new religion based on worship of a

hyper-rational Supreme Being. Rights, asserted on the basis of nothing but

intellectual fads, were trampled as thousands were fed to the guillotine.

Note: I meant to actually post this for Bastille Day... but it was delayed. Oh well. It's my right to delay Bastille Day posts until July 28th, or even Christmas, if I want.

All images- Wikipedia

c David L.

[1]

About choosing the guillotine: when your new government puts this much thought

into the way they’re going to execute people, and just happens to choose a

device that’s supposed to be easy-to-use and lends itself to rapid-succession

executions, warning bells should go off.

No comments:

Post a Comment